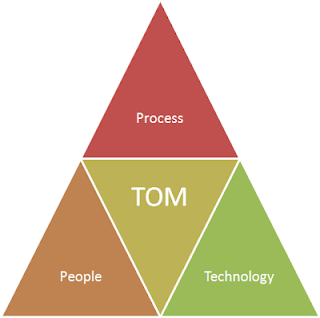

Once you've articulated your strategy, one of the next things to do is to design the organisation to deliver it. This is usually expressed in the form of a Target Operating Model (TOM). A TOM may be for a new organisation you're going to set up, or it may describe the end state for a change programme for an existing organisation.

The general approach is to define the people, processes and technology required to deliver the strategy.

Process

The most common approach for identifying an organisation's processes for creating value is to use Value Chain methodology popularised by Michael Porter. This allows you to identify both

- the core processes, such as manufacturing, sales and distribution, and

- the supporting functions, such finance, IT and HR.

Both types of processes may be essential to the delivery of your strategy.

For each process, it is important to understand

- what the critical success factors (KSFs) and key performance indicators (KPIs) are. That is, what does 'good' look like in the performance of the process.

- what the inputs are and who provides them.

- what the outputs are and who receives or consumes them.

- the type of process: for example, you can classify processes as

- unit or job processes: units of work are processed one at a time from start to finish, like building houses or tailoring suits.

- batch processes: a defined number of units are processed together, like off-the-rack clothing,

- mass production processes: units of work move in sequence through stages, like assembling automobiles, or

- continuous processes: output is continuous, like paper milling.

- anticipated volume and frequency of performance, and drivers of both.

- whether and how the process is required to be performed in a differentiated manner in order to deliver strategic value.

Once you've identified and defined your processes, it should follow naturally what people and technology the processes will need.

People

For each process, identify:

- the roles,

- numbers of people in each role, and

- skills, capabilities and knowledge required by each role.

Consider also whether you will need to:

- hire in new or additional people,

- provide more training to existing people, or

- partner with organisations who already have the types of people you need.

You're then in a position to consider:

- reporting lines,

- organisational design,

- governance and

- rewards (including compensation and benefits).

Don't forget to think about where the people are or will be physically located, and what implications that might have for your organisation.

Finally, consider the impact of organisational values and culture.

See also:

Technology

Technology and systems enable the people to perform the processes.

These include computer systems, manual systems, manufacturing systems and any other supporting technologies.

Do these systems and technologies exist or can you buy, license or rent them? Can you use 'off-the-shelf' systems, or will you have to develop bespoke solutions especially for your business? The more differentiated your processes are the more likely it is that you will need bespoke solutions, or that pre-existing solutions will need extensive customisation.

How will you integrate and maintain these systems? You should be able to map this back to your process view.

Extended approaches

There are a number of different ways in which you could extend this general people-process-technology approach.

Firstly, you could go beyond the convention of considering just people and technology. For example, you could consider all 7 dimensions encapsulated in the McKinsey 7S analysis. People or Staff and technology or Systems are two of the 7 Ses. McKinsey 7S does not emphasise the process dimension.

Secondly, you could adopt the POLISM model developed by Andrew Campbell, and others, at Ashridge Business School. POLISM stands for Process (or value chain), Organisation, Locations, Information Structure and Management system. This gives more prominence to location and suppliers. It considers information and management systems more explicitly than it does technology.

Andrew then went on to propose an integration of the POLISM model and the Business Model Canvas. I have previously written about this in Introducing the Enhanced Business Model Canvas.

The Target Operating Model's role in business strategy execution

Your strategy implementation plan needs to consider all of the implications of the above:

- designing processes,

- hiring, training and motivating staff,

- acquiring or building up knowledge, and

- selecting, implementing, customising, building and/or integrating systems.

Designing a TOM is a significant piece of work. But, the real challenge lies in developing and implementing a TOM which actually

- delivers your strategy and

- differentiates your organisation from the competition.

StratNavApp.com is the online collaborative tool for strategy development and execution. It integrates all of the tools mentioned above: Porter's Value Chain, including Process, People and Technology, McKinsey 7S, and the Enhanced Business Model Canvas. So it can help you develop your Target Operating Model. It is free to use, so go ahead and give it a try.